An estimated 1.9 million people in the United States were diagnosed with cancer in 2022. Treatment options and prognoses vary widely depending on the cancer type and staging, a patient’s overall health, and access to healthcare. Immunotherapy is a promising treatment option but can be extraordinarily expensive and time-consuming. For several years, researchers have turned their attention to a particular feature of some bacteria called the CRISPR-Cas system as a potential tool to improve immunotherapy as an effective cancer treatment.

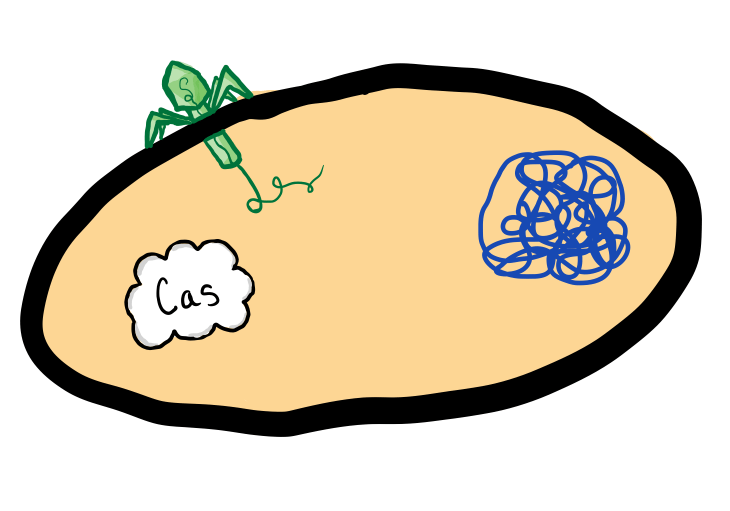

Some viruses target and kill bacteria. Like humans, some bacteria have devised a system to protect themselves against these viruses.

Bacteria that use CRISPR-Cas systems have a special group of proteins called Cas proteins.

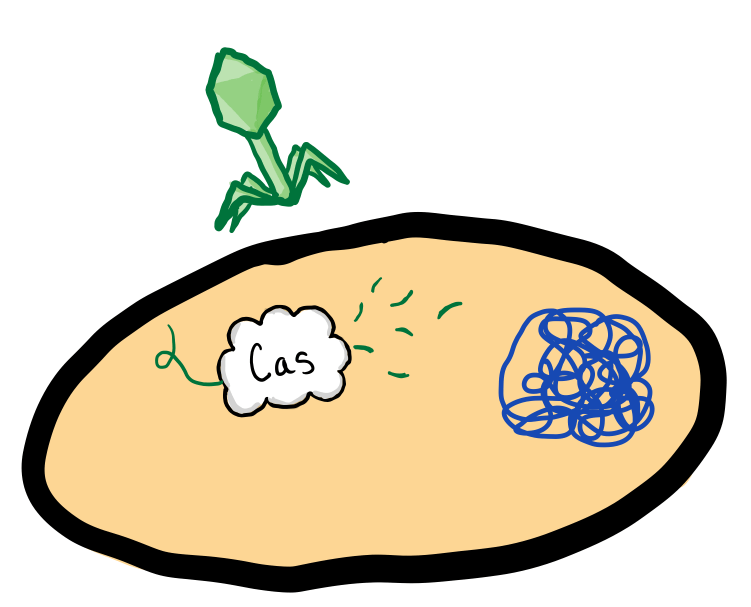

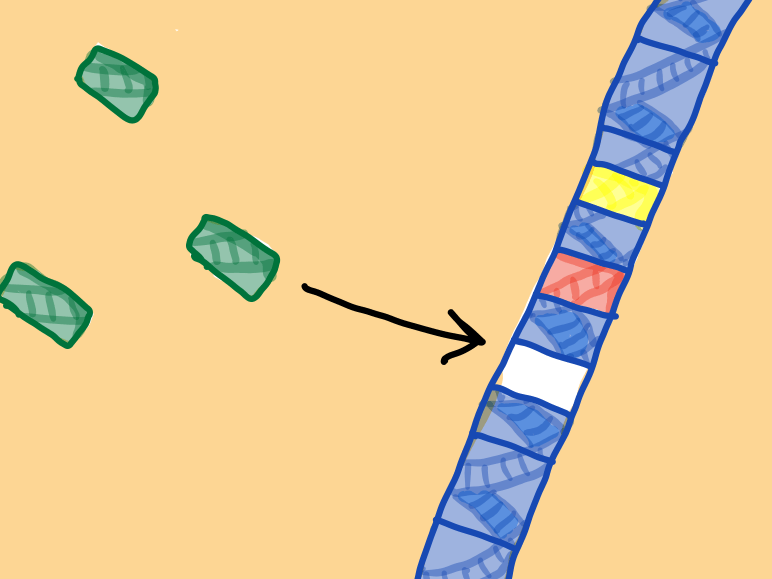

When a virus injects its genetic code into the bacteria, the Cas proteins inactivate the virus by cutting the viral DNA into small pieces. The bacteria insert the viral fragments into a specific section of its DNA. This section, called the CRISPR array, holds a history of the bacteria’s past infections through these small viral fragments.

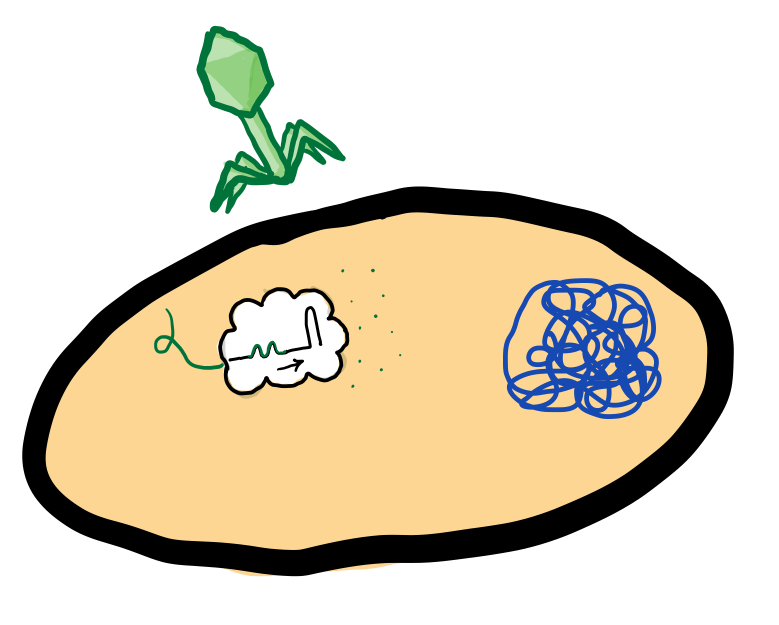

When the same virus tries to infect the bacteria again, the crRNA-Cas complexes bind to the invading virus DNA and kill it.

The historical record of past viral infections is now a part of the bacteria’s DNA. If the bacteria multiply, their daughter cells will also include that history. As a result, they can produce the same crRNA-Cas complexes and protect against the same viruses.

A review in the upcoming March 2023 issue of Life Science investigates the current state of immunotherapy cancer treatment. For years, researchers and physicians have explored CAR-T cell therapy as a potential treatment for many types of cancer, especially forms of leukemia and lymphoma. In CAR-T immunotherapy, cells from the human immune system are programmed to attack specific cancer cells. Unfortunately, these cells are prone to complications. Our bodies may recognize the CAR-T cells as foreign and attack them, as is in the case of Graft vs. Host Disease. The cancer cells can adapt to evade and defend against the CAR-T cells. This is where CRISPR-Cas comes in. The researchers believe they can use the CRISPR-Cas system to make targeted changes to the CAR-T cells and improve their functionality.

Many clinical studies in early Phase 1 utilize CRISPR-Cas-engineered T cells to improve immunotherapy outcomes for treating cancer. Researchers in 2021 presented an overview of the cutting-edge of CRISPR-Cas technology. Their review outlines the early clinical findings from two 2020 studies that suggest that CRISPR-Cas effectively improves outcomes with CAR-T therapy. It’s important to understand that researchers and scientists are studying this technology internationally and that new information could be available any day.

A more recent 2022 comprehensive update on the current state of CRISPR-Cas clinical studies points out an important distinction between studies as results continue to roll in. Many earlier studies focus on taking cells from an individual patient, engineering them using the CRISPR-Cas mechanism, then transplanting the cells back into the individual. Some newer studies are shifting to engineered donor cells, which are less expensive and can serve a larger patient population more quickly. This update points to a 2022 press release from CRISPR Therapeutics. The self-described “biopharmaceutical company focused on creating transformative gene-based medicines for serious diseases” announced promising results from their Phase 1 trial using CRISPR-Cas-engineered CAR-T cells to target lymphoma. Participants in the Phase 1 trial had no reported autoimmune reactions to the treatment, one of the primary concerns for using donor cells.

Genetic engineering comes with the potential moral, and ethical dilemmas often explored in Sci-Fi novels. This technology could mean a medical future in which treatments are tailor-made to cure many of our most devastating diseases. But what comes next? The United States has a long and complicated history of eugenics and scientific discrimination. Beyond that, many Americans struggle to access affordable healthcare. Is this novel genetic engineering available to all who need it? Or would the wealthiest among us continue to receive exclusive treatment? These considerations should be factored into research as clinical trials begin to report preliminary findings.