Estrogen is a well-known sex hormone that frequents news cycles and health literature. This week, we’ll take a deeper look at what, exactly, estrogen is and how it affects our bodies.

StatPearls, one of the principal online resources for medical education, provides an overview of estrogen. Researchers and clinicians work with estrogen under different names like estrone, estradiol, and estriol. These are three forms of the same hormone found in the body. Think of hormones as tiny chemical messengers that send a specific message to targeted cells. The hormone estrogen communicates with and affects nearly every system in our bodies. We usually associate estrogen with developing breast tissue and mammary glands. Estrogen is also responsible for the growth of the cells that line the uterus and vagina. In the uterus, this layer of cells thickens to provide an ideal location for a fertilized egg to implant. In the vagina, this layer provides lubrication. Estrogen also develops long bones (think arms and legs) during puberty and protects bones from breaking down. Estrogen can also reduce the risk of heart disease by increasing the “good” high-density cholesterol and reducing the “bad” lower-density cholesterol.

How does estrogen change over time?

I recently listened to an interview with Dr. Sara Gottfried, former gynecologist turned sports medicine, on an episode of Andrew Huberman’s podcast, Huberman Labs. Gottfried makes a strong argument for tracking estrogen levels as she believes that estrogen can significantly impact not only reproductive health but also neurological and intestinal health. She claims that our hormone levels, particularly estrogen, fluctuate until the end of adolescence. Interestingly, Gottfried shares that she has heard that adolescence extends to age 25. I traced this to a 2018 opinion piece in The Lancet. The authors of that piece argue for an extended adolescent range as we see a delay in social transitioning to adulthood at a population level. While there is no global consensus on what defines adolescence, the World Health Organization uses ages 10 to 19 as their adolescent range. In the United States, the American Academy of Pediatrics breaks down adolescence into three periods: early adolescence (10 to 13), middle adolescence (14 to 17), and late adolescence (18 to 21 or later).

One 2020 study published in the Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism seeks to create defined estrogen ranges from infancy through menopause and beyond. Their study showed a spike in estrogen levels in genetically female infants at three months old. All of the children in the study had comparatively low estrogen levels until around ten years old when estrogen levels rose significantly in genetically female children. Estrogen levels in genetically female adolescents peaked between ages fifteen and sixteen and remained “relatively constant” for forty years. The study then showed a significant decrease in estrogen in genetically female participants after age fifty-five. While researchers noticed consistent trends in the study’s population, individual participants had widely different estrogen baselines. This could support Gottfried’s testing for estrogen levels, especially as a young adult, once the early fluctuation of hormones has stabilized.

Estrogen as Birth Control

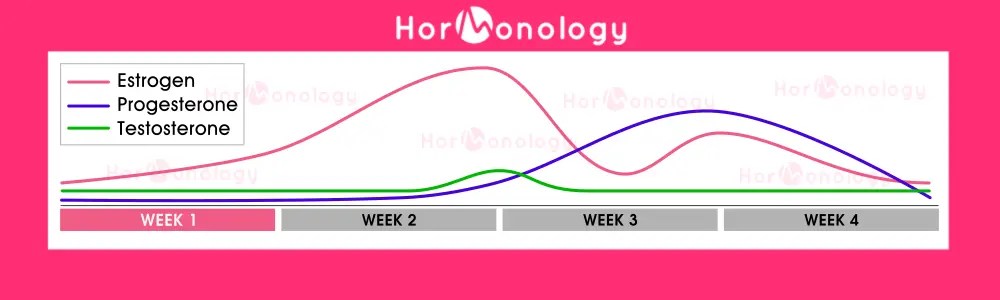

To fully understand how we use estrogen as birth control, we have to start with the hormone cycle of menstruation. Merck manuals provide medical education resources to both healthcare professionals and patients. Their 2022 edition details the progression through puberty and a step-by-step breakdown of a typical period. As estrogen levels in an early adolescent rise, breast tissue develops slightly, a process called “breast budding,” and we see an initial growth spurt. Then, hair grows on the genitals and armpits as the growth spurt peaks. Two to three years after the beginning of breast development, we enter our first menstrual cycle, the menarche. Merck states that it can take up to five years for menstruation to become regular while simultaneously body fat increases and the pelvis and hips widen. Doctors consider a period every 21 to 35 days clinically “normal,” with the average time between periods at about 28 days. In the first week or so of a typical menstrual cycle, the bleeding portion of a period, estrogen levels remain very low. In the second week, estrogen levels rise exponentially. When estrogen peaks at the end of the second week, the ovary responds to the high estrogen level. It releases an egg in a process we call ovulation. For the next two weeks, estrogen stays high to thicken the uterus and maintain a healthy uterine lining for the potential fertilized egg. At the end of these two weeks, estrogen levels drop. At this point, the uterus contracts and expels the uterine lining, causing bleeding that brings us back to the beginning of the menstrual cycle.

So how do we use estrogen to prevent pregnancy? The typical formulation of an oral birth control pill includes both estrogen and a related hormone called progesterone. StatPearls describes how they work in detail. Progesterone and estrogen inhibit or block the production of other hormones responsible for developing and releasing an egg from the ovary. Without an egg, the body cannot ovulate or become pregnant.

Despite being an effective method of birth control, oral contraceptives are not without risks. In her interview with Huberman, Dr. Gottfied cautions against using oral contraception. She claims that the progesterone component of the birth control pill is “dangerous and provocative.” The National Health Service of the United Kingdom outlines the significant known side effects of oral contraceptives, including headache, nausea, breast tenderness, mood swings, increased blood pressure, increased chance of developing blood clots, and increased risk for breast cancer. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists provide a similar list of possible side effects of hormonal birth control methods, including a “small increased risk” of deep vein thrombosis, heart attack, and stroke, especially in women over the age of 35 and women who regularly smoke cigarettes. Dr. Gottfried specifically references the Women’s Health Initiative as the primary source for her claims. A well-known 2002 study from the Women’s Health Initiative did find some significant risks with the use of progesterone. However, the study focused on older adult patients using prescribed estrogen and progesterone to treat the symptoms of menopause.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

In a 2013 Women’s Health Initiative study, participants taking a combination of estrogen and progesterone to treat symptoms of menopause saw an increase in the risk of both breast cancer and heart attack compared to participants taking only estrogen. Patients farther into menopause when they initiated hormone therapy saw even greater risk. Overall, the study questioned the safety of hormone replacement therapy in its current form, favoring estrogen-only hormone replacement in younger women. This is consistent with Dr. Gottfried’s recommendation to consider early hormone replacement therapy with estrogen.

So What?

Estrogen is an essential hormone for the normal growth and development of the human body. It’s important to understand how estrogen works for us and how to recognize when our estrogen may be working against us.