What is a Bone Marrow Transplant?

In its simplest form, a bone marrow transplant replaces bone marrow. Bone marrow is found inside some of our bones and is soft and spongy. Some bone marrow, red bone marrow, actually houses the special cells that become all of our blood cells.

The American Cancer Society provides an overview of these special cells called “hematopoietic stem cells” and how transplanting these cells can be life-saving for some people. Hematopoietic is a medical term for blood-forming. For simplicity, we will refer to these cells as blood stem cells. Blood stem cells live in the bone marrow, where they mature until the body needs them to become a particular type of blood cell. Blood stem cells can become red blood cells, white blood cells, and even tiny cell fragments called platelets. Blood stem cells are critical to human life and need to be replaced when those cells are damaged or destroyed by disease, cancer, and medical treatment. Suppose the patient has a compatible bone marrow donor. In that case, the donor is sedated, and some bone marrow is removed from the donor’s bone (often the pelvis). The donated bone marrow may be filtered and frozen until it is ready to be used when it is thawed and given to the patient through an IV. Transplanted blood stem cells from donor bone marrow set up shop in the recipient’s bone marrow to hopefully go on to produce healthy blood cells.

Who Needs This Kind of Transplant?

Johns Hopkins Medicine outlines a host of reasons why a person may need a bone marrow transplant, including replacing bone marrow that has been destroyed by disease, as we have already discussed. Bone marrow transplants can also replace a patient’s immune system, as many of the critical defenses of our immune system come from our white blood cells. In a 2022 clinical protocol update, the European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation outlines the most common indications or reasons a healthcare provider should recommend a bone marrow transplant. Their exhaustive list includes many forms of anemia, leukemia, lymphoma, autoimmune disorders, and neurological conditions like myasthenia gravis and multiple sclerosis. In addition, an overview of stem cell transplants from the American Cancer Society stresses that transplantation is a necessary treatment for leukemia, lymphoma, and multiple myeloma. In these cases, cancer cells have either grown in the bone marrow or spread to it. The donated blood stem cells allow the patient’s body to “start over” with healthy blood cells and hopefully wipe out the cancer cells.

Who Can Donate Bone Marrow?

Johns Hopkins Medicine explains that some patients can donate bone marrow to themselves. In this process, the patient’s bone marrow is removed, filtered, potentially frozen, thawed, and reintroduced to them through an IV. When a patient donates their own bone marrow, we call this an “autologous” bone marrow transplant or rescue. Other times, doctors and patients must wait until they can find a compatible donor with healthy bone marrow. Bone marrow transplants from a genetically compatible donor are called “allogeneic” bone marrow transplants. Doctors will often look at a patient’s siblings as potential donors and very rarely may find a match in the patient’s parents. Unrelated yet genetically compatible donors can be found through registries like the international Be The Match registry.

What Does it Mean to Be A Match?

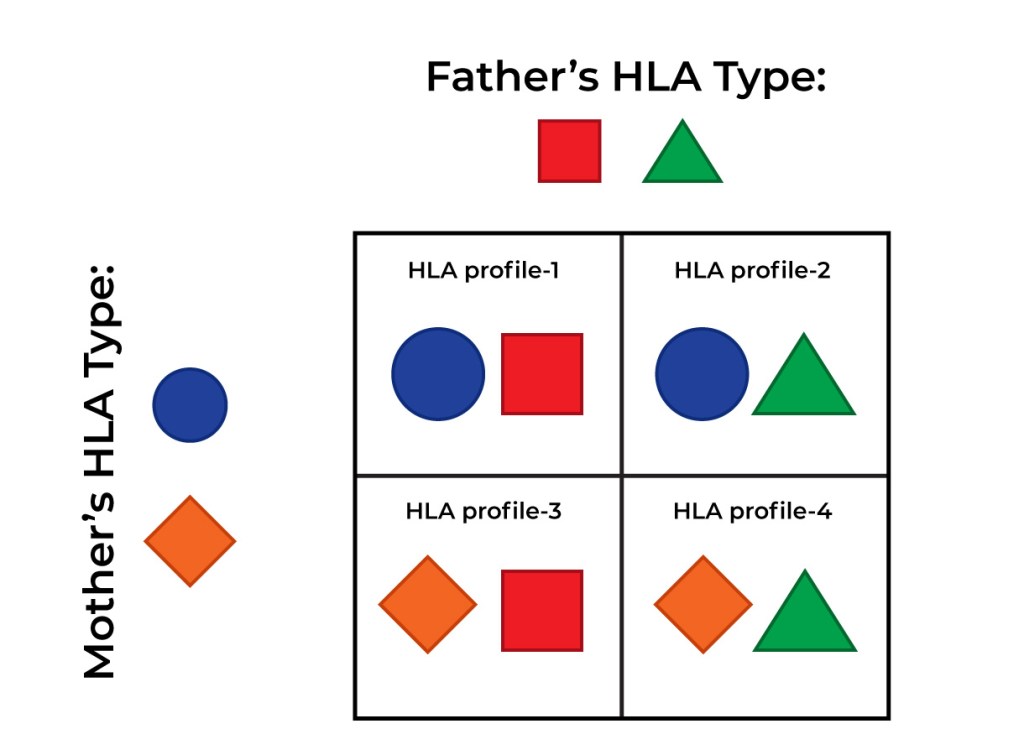

When looking for a genetically compatible match, we focus on a particular group of genes. The European Society for Blood and Marrow Transplantation explains that the ideal donor is an identical genetic match to the patient’s “HLA” genes. Blood cells critical to the immune system express two classes of HLA genes. A 2019 clinical update on genetic matching for stem cell transplants focuses closely on these HLA genes. The HLA Class 1 genes are expressed in every cell in our bodies. When considering donors, we look specifically at HLA-A, HLA-B, and HLA-C. The HLA Class 2 genes are the genes that are only expressed on important blood cells in our immune system. Here, we look for matches at HLA-DRB1, HLA-DQB1, and HLA-DPB1. The acronyms here are not nearly as important as what they signal: to find a compatible bone marrow donor, doctors have to focus closely on this small set of genes and hope for a match.

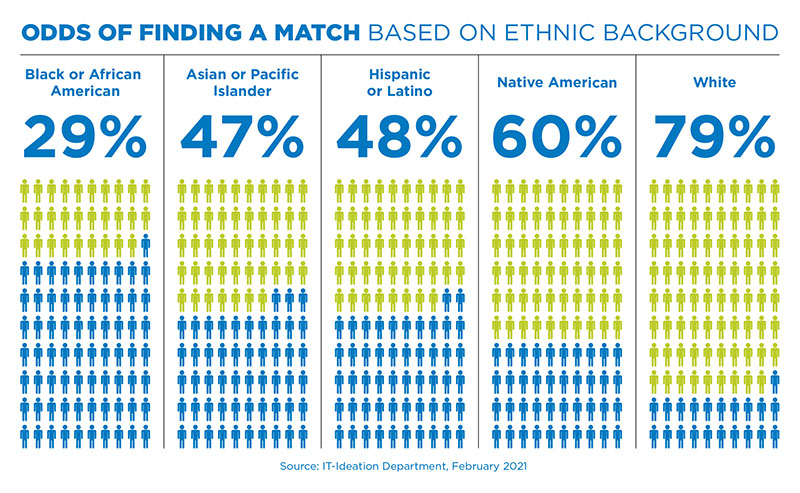

Fortunately, there are ways to narrow down our search for donors to just the most likely matches. Unfortunately, based on the pool of people who have registered, some ethnicities and races are less likely to find a donor through the registry. Be The Match, a non-profit organization that connects stem cell donors to recipients, discusses how ethnic background affects genetic compatibility. We inherit our HLA genes from our biological parents, who inherited them from our grandparents. This is why our siblings are our most promising genetic matches for stem cell donation. As of February 2021, the odds of finding a genetically compatible donor as a white patient were 79% compared to a Black or African American patient at only 29%. This significant disparity has increased marketing towards non-white racial and ethnic groups. The more diverse the donor registry becomes, the more likely it becomes for a patient from any ethnic background to find a match.

Stem Cells from Umbilical Cord Blood

Another alternative for allogeneic sources of stem cell transplant is umbilical cord blood. The Leukemia and Lymphoma Society provides information on cord blood banking for potential pregnant donors. Umbilical cord blood is similar to bone marrow in that it contains many hematopoietic or blood stem cells. Doctors collect blood from the umbilical cord and placenta shortly after a baby is born. The blood is then frozen and stored in a cord bank until needed. Babies with leukemia usually cannot use their banked cord blood and benefit significantly from donated cord blood from another source. As of their most recent policy statement in 2017, the American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that pregnant people consider a public cord blood bank over private banks. Public cord blood banks are free to use and make their donations globally available to genetically compatible recipients. Private cord blood banks store the blood for an individual family’s later use at a high financial cost.

The choice to donate stem cells in any form is incredibly personal. Of course, there are significant life-saving benefits to bone marrow transplants. Because patients must be close genetic matches, we must encourage donors from all ethnic and racial backgrounds. However, donation of any kind is not without risk. Only you can decide if stem cell donation is right for you.

For more information on becoming a stem cell donor, see the links below:

I am not associated with any of these groups in any way. I receive no compensation for linking to these organizations. These links are purely here as resources for more information should you choose to use them.